Mapping the Republic: How ROC Cartography Shaped the Borders of Ladakh and Beyond

Asia Communique Essay

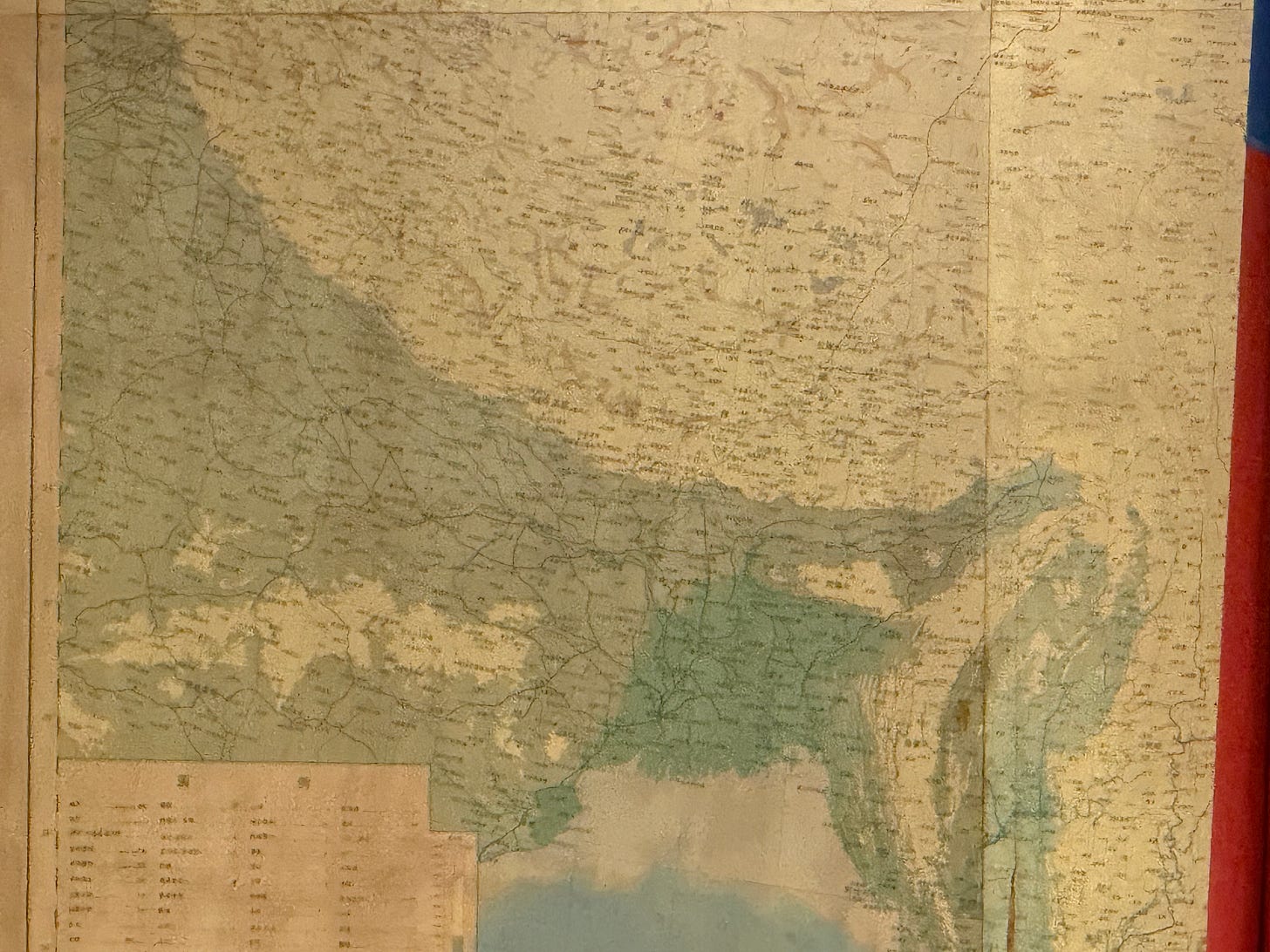

Map at the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall

Maps are never neutral. They tell us more than where mountains and rivers lie — they embody state power, ambition, and memory. For the Republic of China (ROC), which retreated to Taiwan after 1949, maps became both a political claim and a national myth. Framed wall maps still displayed in Taiwan today do not stop at the island’s coast. They sweep across all of mainland China, encompassing Tibet, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia. They even extend into contested frontiers with India, including Arunachal Pradesh and Ladakh.

Looking at these maps today helps explain the roots of Himalayan disputes. They reveal not only the ROC’s inheritance of Qing dynasty frontiers but also how, over time, cartography hardened into a tool of sovereignty and defense. The evolution of maps between the 1910s and the 1940s shows how borders shifted on paper long before they hardened on the ground.

The ROC’s Inheritance

When the Qing dynasty fell in 1911, the newly established Republic of China claimed to inherit the Qing’s territorial sovereignty, including frontier areas such as Tibet, Xinjiang, and loosely governed zones like Aksai Chin and parts of what is now Arunachal Pradesh.

In its treaty policy, the ROC rejected instruments it regarded as imposed by colonial powers. Notably, it refused to ratify the Simla Convention (1914), under which Britain and Tibet drew the McMahon Line. Because China never accepted the agreement, the ROC did not recognize the McMahon Line as legally binding.

Earlier in the 20th century, British boundary proposals—including the Johnson Line and the Macartney–MacDonald Line—that would place Aksai Chin under British Indian control were never formally accepted by China. In practice, some early ROC maps did adopt the Johnson boundary in the Aksai Chin region. Over time, however, ROC cartography gradually shifted to reflect the nationalist posture of an unbroken China extending to the Himalayan frontier, abandoning earlier reproductions of British survey lines in favor of expansive claims.

Early Cartography: The Postal Atlas (1917–1933)

The Postal Atlas of China (郵政輿圖), published in 1917 and updated in 1933, was one of the most influential mapping projects of the early Republic. Produced by the Ministry of Communications, it guided the postal service but also served as a quasi-official delineation of territory.

In these atlases, the Ladakh frontier followed the Ardagh–Johnson Line, drawn by British India in the 19th century. This line placed Aksai Chin within India’s territory. In other words, the ROC’s own maps — despite its refusal to accept British treaties — depicted Aksai Chin as Indian.

This contradiction underscores how, in the 1910s and 1920s, the ROC lacked both the resources and the political will to impose a uniform territorial claim in its cartography. The maps were practical tools first, instruments of sovereignty second.

The 1930s Shift: Mapping for a State under Siege

By the mid-1930s, the geopolitical situation changed dramatically. Japan had seized Manchuria in 1931 and was encroaching deeper into China. At home, Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government sought to centralize control, modernize the economy, and prepare for war.

It was in this context that the National Resources Commission (資源委員會, NRC) — a powerful technocratic agency established in 1935 — undertook a sweeping mapping program. In 1936, the NRC published a 1:1,500,000 scale national map series, covering all of China and its borderlands.

The archives of Academia Sinica confirm the existence of this complete set. The NRC maps were single-color prints but ambitious in scope. They were not just geographic references; they were part of the NRC’s wider mission to inventory China’s natural resources, plan infrastructure, and prepare for industrial mobilization in wartime.

In these maps, the frontiers began to shift. Unlike the Postal Atlas, which sometimes mirrored British survey lines, the NRC series increasingly shaded Aksai Chin inside China’s territory, assigned to Xinjiang or Tibet. For the first time, ROC official cartography aligned with its nationalist rejection of the Johnson Line.

The timing was no accident. As Japan expanded, the ROC needed maps not only to plan resource exploitation but to claim sovereignty over every corner of its territory. Cartography was becoming an instrument of defense.

The Resource Map: How Economics and Territory Intertwined

Among the most revealing artifacts of Republican cartography are not the grand wall maps for classrooms or ministries, but the more technical charts produced for state planning. The map shown here, titled 「資源調查分布圖」 (Resource Survey Distribution Map), comes from the mid-1930s, when the National Resources Commission (資源委員會) was created to mobilize China’s economy under the looming threat of Japanese expansion.

At first glance, the map looks like a standard geographic reference. Provinces are outlined, rivers traced, and railroads carefully inked. But its real purpose is in the title: to identify and visualize the distribution of key resources—coal mines, mineral sites, and industrial nodes—across the Republic of China. The two inset maps at the bottom break down regional concentrations in greater detail, likely zooming in on particular basins or industrial clusters.

What makes this map significant is how it blends resource planning with sovereignty claims. The territorial outline encompasses all of China as defined by the Republic of China—from Manchuria and Inner Mongolia, down through Xinjiang and Tibet, and including Taiwan. That means the disputed frontiers with India, such as Aksai Chin in Ladakh and the McMahon Line in Arunachal Pradesh, are silently absorbed into the ROC’s vision of national territory. Tibet is mapped as an integral unit, its borders drawn without acknowledgment of India’s competing claims.

This is more than symbolism. By embedding disputed regions within a framework of economic geography, the ROC made a statement: these territories were not just lines on a map, they were part of the nation’s industrial future. Railroads etched into remote provinces implied a destiny of integration, even if the state lacked actual control on the ground.

Seen alongside the Postal Atlas (1917–1933), the NRC’s national series of 1936, and the Ministry of National Defense’s maps of the 1940s, the Resource Survey Distribution Map marks a turning point. Earlier cartography was often inconsistent, at times reproducing British survey lines. By contrast, resource maps like this were unapologetically maximalist—they aligned with Qing-era territorial inheritance and ignored foreign treaty boundaries.

For readers today, this map illustrates the logic of cartographic statecraft in Republican China. Territory was not mapped only to show sovereignty. It was mapped to be planned, exploited, and mobilized. The inclusion of Tibet and Xinjiang was not a footnote—it was a cornerstone of national survival, linking resources in the frontier to the defense of the Republic.

Placed in the broader sequence of ROC cartography, the Resource Survey Distribution Map shows us that by the mid-1930s, the Republic’s claims over Ladakh and Arunachal were no longer abstract lines but embedded in the state’s vision of industrial mobilization. In this way, the Himalayan disputes we see today are tied not only to military or political history but to the economic cartography of a state under siege.

Wartime Cartography: The Ministry of National Defense (1943–1947)

During the Second World War, with the ROC government relocated to Chongqing, the Ministry of National Defense (國防部測量局) issued a new 1:1,000,000 scale map series between 1943 and 1947. These were more detailed, multi-sheet maps designed explicitly for military and administrative use.

On these maps, there was no ambiguity. Aksai Chin was firmly inside China. The border ran west of the plateau, leaving only Leh and Kargil — the populated parts of Ladakh — outside ROC territory. Tibet, too, was shown as fully Chinese, extending into South Tibet (today’s Arunachal Pradesh).

By the 1940s, ROC cartography had completed its shift. The earlier contradictions were gone. The maps now reflected the nationalist conviction that all Qing territories remained Chinese, regardless of British or Indian claims.

The 1947 National Wall Map

After Japan’s defeat, the ROC sought to reassert its sovereignty at home and abroad. One product of this moment was the Zhonghua Minguo Quantu (中華民國全圖), a national wall map published in 1947.

This map, used in schools, government offices, and embassies, portrayed the ROC as a unified state stretching from Manchuria to Tibet. Its boundaries echoed those of the defense maps: Tibet incorporated, Arunachal Pradesh included, and Aksai Chin shaded within China.

Even after 1949, when the ROC government retreated to Taiwan, these wall maps remained symbols of legitimacy. Displayed with the ROC flag, they asserted that the Republic of China still represented all of China, not just Taiwan.

What the Maps Explain

When viewed together, these maps tell a powerful story.

1. The ROC and PRC share the same inheritance.

Both governments trace their territorial claims to the Qing dynasty’s borders. Despite their rivalry, their maps of Tibet, Ladakh, and Arunachal Pradesh are strikingly similar.

2. Claims hardened over time.

The 1917–1933 Postal Atlas followed British survey lines, effectively giving Aksai Chin to India. By the 1936 NRC maps, and certainly by the 1940s defense maps, the ROC had shifted decisively to include Aksai Chin within China.

3. Cartography became part of defense.

Especially from the mid-1930s onward, mapping projects were tied to national survival. The NRC’s 1936 national map was not just about geography; it was part of a broader mobilization for war and industrial planning.

4. Borders on paper shaped disputes on the ground.

Today’s Sino-Indian tensions over Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh are not just PRC policies. They are rooted in ROC-era maps that first drew these claims with confidence.

Why This History Matters

Understanding ROC cartography matters because it shows that the contested borders of the Himalayas predate the People’s Republic. When Beijing rejects the McMahon Line or claims Aksai Chin, it is not inventing new lines. It is following the cartographic precedent set by the ROC in the 1930s and 1940s.

For India, this history underscores why the dispute is so intractable. China’s claim is not just a Communist Party position but a century-old inheritance embedded in official maps.

And for Taiwan, these maps remain awkward symbols. Constitutionally, the ROC has never abandoned its claim to all of China. But in practice, these claims are vestiges of a bygone era, framed on walls but disconnected from political reality.

Conclusion

Maps are artifacts of power. The ROC’s cartographic history — from the Postal Atlas of 1917 to the NRC’s 1936 national maps, to the defense surveys of the 1940s — shows how China’s Himalayan borders hardened on paper before they hardened on the ground.

In Ladakh, the ROC shifted from acknowledging Aksai Chin as Indian in the 1910s to claiming it as Chinese by the 1930s. By 1947, that claim was fixed in national wall maps that still hang in Taiwan.

For readers today, these maps explain why disputes over Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh remain so persistent. They are not just the product of contemporary geopolitics. They are the legacy of how a government — first in Nanjing and later in Taipei — chose to draw its maps.

If you like this deep dive, please let me know!