Nehru hoped India and China could work together for good of world at large, says Bhasin (author of Nehru, Tibet and China)

An interview with Avtar Singh Bhasin

Avtar Singh Bhasin is the former Director of the Historical Divison of the Ministry of External Affairs. He was posted to Indian missions in Nepal, Bonn, Vienna and Lagos. He has also travelled to several other countries as part of his service at the Ministry. Since his retirement, Bhasin has engaged in academic research and tracking down archival material, which can contribute to collective understanding of recent history of India and relations with other countries.

Bhasin has just published a new book titled Nehru, Tibet and China. In the book, Bhasin tries to fill the gap in our understanding about India-China relations with the help previously inaccessible Nehru Papers.

If you are interested in buying the book, you can do so here.

You have written extensively on India-China relations, including a five-volume study on India-China Relations from 1947-2000. How did you come to take interest in China and Tibet?

After my retirement in 1993 when I had taken to academic research, I found that there was a big lacuna in the research material for studying conduct of India’s Foreign Policy or relations with the neighbouring countries. The Ministry of External Affairs had put a tight lid on its records, which had led to our skewed understanding of India’s policies particularly towards neighbours. I undertook upon myself to fill this gap. Starting with Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Nepal, I published 5-volume each of documents on India’s relations with these countries. This was followed by a 10-Volume study of India-Pakistan relations. That had left out China since the archives on China were too tightly shut that it was not possible to even peep into them. Outside the official archives of the MEA there was a collection of papers, called ‘Nehru Collection’ which was lying in the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library which too had remained shut and inaccessible for research until 2014, when this collection came under the jurisdiction of the Department of Culture, I sought permission which was granted.

Going through the collection I found it a treasure trove. The papers were highly classified and were mostly Nehru’s own telegrams, notes and letters on the issues which he dealt with during his prime ministership from 1947 to 1964. The largest number among them were papers dealing with China. The papers on China selected from this source together with those harvested from other sources, like Haksar and Subimal Dutt papers made a big collection worthy of publication. These were published in five volumes in 2018. After a careful and deeper study of these papers, I found the history of those crucial years under Jawaharlal Nehru as known to us was totally asymmetrical to the facts emerging from these papers.

I was in a dilemma whether or not to write a book based on facts emerging from these papers. The story which I pieced together from these papers runs counter to the stand the Government of India had taken particularly on the frontiers with Tibet/China. I reasoned that living with the past narrative we have already fought a war and continuing to live with it had failed to resolve the issue in the last six decades and perhaps it would continue to hang like sword of Damocles on our head. That was the trigger for this book. It is hoped the people of India would carefully study those events and allow the Government to seek a modus vivendi to resolve the imbroglio.

2) In the preface of your book, you quote Prime Minister Nehru’s remarks made in the parliament on 12 June 1952: “because the success or failure of any foreign policy today involves the success and failure of the whole world”, said Nehru. Do you think that worldview ran into a problem when it came to Mao’s China? How much do you think that worldview informed Nehru’s relationship with China?

It did not run counter to his world view. I think Nehru was of the firm opinion that China and India working together would ensure world peace. He particularly looked at India playing a leadership role in the world for which peace was important. Even before independence on 25 December 1945 while addressing the Sino-Indian Cultural Society at Shantiniketan he had said “we hope that the present state of affairs in India and China will end and both the countries will come closer in their friendship not only for mutual advantage but also for the good of world at large”. In a press interview on 23 December,1945 he said ‘when there will be free India, I should very much like the development of closer contacts with China, cultural and political’. In August 1946, Nehru again said “India is going to be the centre of a very big federation, which would include China, South East Asia and also West Asia”. In August 1946, he projected India in the leadership role and said “there has been a tendency for many of dependent countries of Asia and Africa to look towards India for leadership in their attempt to attain political and economic freedom”.

After independence he asserted India held a position in the world that in every way qualified it for a permanent seat in the Security Council and even if India did not get that seat, it did not prevent him rating India’s overall influence within the United Nations as quite high. To play such an important role as that of a world leader of peace was a prerequisite hence his stress on world peace even if in the process India’s own interests were sacrificed.

3) How would you describe Jawaharlal Nehru and Zhou Enlai’s interactions through in-person meetings and letters leading up to the 1962 war. Is there something historians have missed so far that you have attempted to add with your new book?

They met four times in person apart from exchanging correspondence. In 1954, Zhou Enlai came to India and in October of the same year Nehru visited China. Zhou came again in December 1956- January 1957 when Dalai Lama was also in Delhi, it was suspected that Dalai Lama might take asylum in India and not return to Lhasa. They met fourth time in Delhi when Zhou came to India for border talks.

The first two meetings in Delhi and Beijing were quite friendly when they discussed mostly international issues and avoided any bilateral matters. The third time again most of the discussions were centred on international issues. Zhou this time primarily wanted to discuss the issue of Dalai Lama seeking asylum in India. He too showed his anxiety at the simmering discontent in Tibet at the Chinese occupation and blamed it on Tibetans settled in Kalimpong and wanted Nehru to take cognisance of it. Nehru took the whole thing lightly and said Kalimpong was the nest of spies and there were more spies there than the residents. But it caused a lot of bad blood between the two countries. Zhou Enlai was a suave diplomat who knew how to get his point of view across without offending the other party. He was a matter of fact person and had little pretensions to be a world leaders. His effort always was to get his point of view across as politely and diplomatically as possible and allow the other person to take credit.

Basically, the people had a skewed idea of India-China relations since the facts were not in the public domain and the reach of media, in the absence of internet in those days, was extremely limited. Nehru had a very venerable position in the country and his policy of non-alignment had gathered a lot of attention internationally. Almost all the African and Asian countries had come within the ambit of non-aligned movement, since it was a fit all size organisation with no commitment on their part. This gave him much larger profile than the resources of India commanded then. This of course was not to the liking of China as later developments indicated. Later, when India stood for calling the first non-alignment conference, China favoured a second Bandung type Afro-Asian Conference. The holding of the first non-alignment conference in 1961 at Belgrade created some misunderstanding between the two countries and China started undermining the Indian role in world affairs.

4) In chapter 7 ‘India-China agreement on Tibet’, you write that China maintained an ambiguity by rebuffing efforts to even discuss the issue of trade with Tibet via Ladakh in 1954. China maintained that the issue of Ladakh was tied to the issue of Kashmir back in 1954, as you have mentioned in your book. China had intriguing deference to Pakistan’s stake in Kashmir. What explains that deference based on your research? How does that deference inform China’s more recent actions in Ladakh since April 2020?

A large portion of Jammu & Kashmir’s territory was in Pakistan’s occupation and that area was contiguous to China’s Xinjiang Province. It was perhaps China’s strategic thinking that at some future date it could give China a very useful link to the sea. It was also a signal to India that it cannot take China for granted and it would stay neutral between the two neighbours. This also gave Pakistan a signal that China was not sold to India and there was a scope to wean China away from India by offering it strategic advantage to it. If you see the progress of China-Pakistan relations they had hardly any area of conflict and both countries were responding to friendly overture of each other. Even when Pakistan had joined the military alliances against Communism, China readily accepted its explanation that these alliances were not against China but against India’s malevolence towards Pakistan. And, that thinking is predominant in today’s leaders of China as well.

5) In the chapter titled “The Chinese Occupation of Tibet”, you talk about a potential intervention by the US as a justification provided by China to intervene in Tibet. President Xi Jinping has spoken about securing the border areas and strengthening national security vis-à-vis Tibet. Do you think similar concerns to what we saw back in the 1950s are at play today with the kind of geopolitical competition unfolding between the US and China?

It was not U.S. intervention in Tibet as such which worried the Chinese since Chinese knew the American could not intervene in Tibet without India’s cooperation, and they had ruled out this possibility. Even now the Chinese are pretty sure that the United States could do it no harm in Tibet and American attempts to create problems in Tibet by training Tibetan guerrillas too had failed. In the early fifties, it was other external factors such as the Korean war, and the American bombing of Manchurian towns together with the uncertainty of the arrival of Shakbpa mission which led China to end the Tibetan uncertainty at least. Nehru in his letter of 1st November 1950 to the Chief Ministers of the Indian States had said: “it was due to the American bombing of Manchurian towns, which made China believe that they were under threat and they responded to these real or fancied enemies”. Now the Chinese have no fears of any country creating trouble in Tibet except perhaps India.

As regards to the second part of your question, China continues to be worried about the internal situation in Tibet. It is indeed true. What is galling to them is that the Tibetans even after almost three-quarter of a century of Chinese occupation and after undertaking huge infrastructure project and social welfare schemes costing billions are not reconciled to the Chinese occupation and one hears reports of Tibetans defying the Chinese administration now and then. The Chinese concerns are internal and real.

6) Despite getting a favourable treaty in the Panchsheel Treaty of 1954 China was somewhat paranoid about giving India access to Tibet via the trade passes in Ladakh, as you have mentioned in the book. Zhou Enlai told the National People’s Congress in April, 1962 that India was trying to usurp Chinese territory which was mentioned in the context of Ladakh. Did China see whole of Ladakh region as its own territory? Or was there certain boundary claim in Ladakh that was particularly of interest to China?

By not agreeing to give a direct route for Ladakh’s trade with Tibet, China sent a message to Pakistan that it should not write it off as a friend. It thereby won Pakistan’s gratitude. There was something more to it. Since Pakistan-occupied area of Kashmir had given China contiguity to Pakistan, taking a long-term strategic view of geography, China saw many new possibilities for itself in the future. It saw the possibility of finding a short route to the sea by linking its Xinjiang Province to the Arabian Sea. This motivated China to first construct a port on the Arabian Sea at Gwadar and then undertaking the development of the entire region with a massive investment of $60-billion, under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

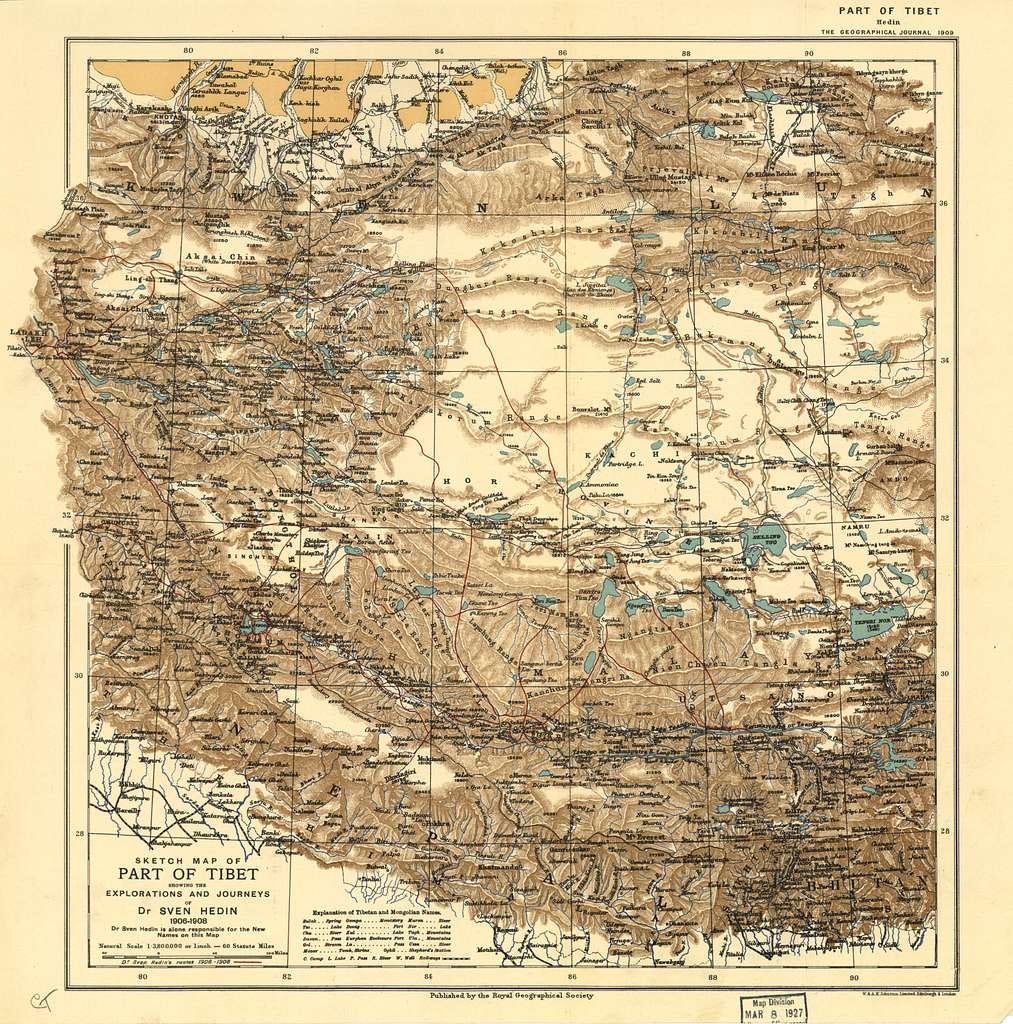

In this context, we have to remember the Aksai Chin area which borders Ladakh was a disputed territory and the border in this area was marked as UNDEFINED in the Survey of India’s maps when India became independent in 1947. The Survey of India maps reprinted until 1954 continued to show border as UNDEFINED. However, in 1954 under instructions from the Prime Minister Nehru a line was drawn unilaterally showing the border as defined. Having done that India did not set up any check-posts in the Aksai Chin leaving a vacuum. Since, it was strategically important area for China which gave it contiguity to Tibet and it had constructed a road to link Sinkiang with Tibet through Aksai Chin, it asserted its claim on the basis of occupation and other factors. The unilateral action of India created a problem which was trigger for the war later.

7) From the book, I get the sense that Nehru gave up on the idea of independent Tibet early on. Do you think a different outcome for Tibet could have been achieved?

Nehru was resigned to China occupying Tibet but it had to be done by peaceful means while respecting Tibetan autonomy. I don’t think any different outcome was possible at that stage. Any aggressive response was not possible given the state of Indian army, which had been split at partition, had exhausted its limited resources in Kashmir operations with little possibility of their replenishment and bulk of the force having been demobilised.

8) Are there any other archival documents yet to be made public that could improve our collective understanding of the early history of India-China relations?

Yes, there are many more documents yet to see the light of the day. While they could add to our understanding of those events somewhat better, they would not change the basic premise.

9) Could you please recommend any books that you think anyone interested in history or International Relations should read?

There is no dearth of books on various aspects of the history of China and Tibet and also on India’s relations with China. It all depends on the individual’s interest as to what aspect of the subject he wants to study and one’s interest generally. The latest additions has been Shivshankar Menon’s book titled: India and Asian Geopolitics; The Past and Present.